Originally for “Rituals of Play in a Global Pandemic” for Freeplay 2020 on June 13, 2020.1 Content warning: discussion of police brutality.

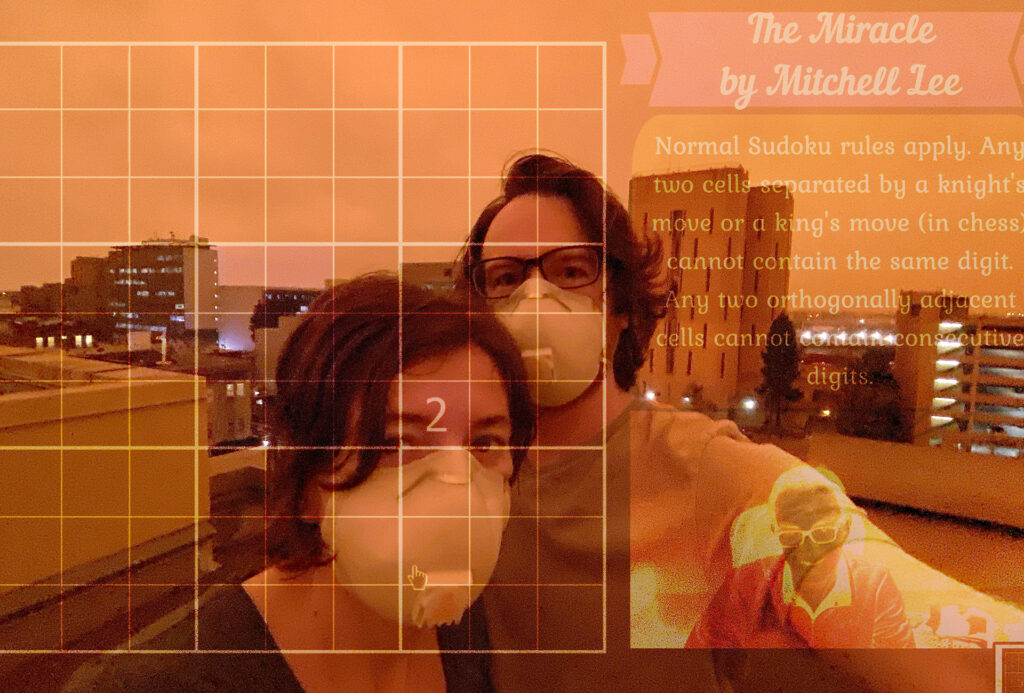

Today the sky turned orange.2 It’s September 9, and smoke from California’s many wildfires (one sparked by the pyrotechnics from a gender reveal party in Yupica, just east of LA) is filtering the sun in the East Bay. Our apartment was already sealed with strips of blue painter’s tape due to tens of thousands of dry lightning strikes3 that ignited California over the summer but, even with the tape, our ad hoc air purifiers—HEPA filters duct taped to box fans—are starting to look a little dusty. Luckily we have plenty of masks: valved N95s for the smoke, surgical 3Ms for Covid-19, black bandanas for protesting. On May 29, four days after George Floyd was killed, Oakland moved from social distancing to social justice. 15,000 people marched in masks4 and the Oakland Police Department responded by imposing a curfew on top of the quarantine then using it to systematically tear gas, flash bang, and sting-ball protesters.5 Outside looks like hell, so we’ve been living inside for 182 days. Exactly 26 weeks alone in our apartment. Half a year living with air that turned lethal in so many different ways. A year of pandemics, protests, pyrotechnics… and play? Slow then sudden. Bored then scared. Playing Sudoku while hearing sirens, while smelling smoke, while social distancing. The emotional and cognitive whiplash between the inside and the outside, the private and the public, the local and the global of this particular moment is but one symptom of the precarity of 21st century life.

In Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay “The Imagination of the Disaster,”6 she writes that the Cold War brought together the “continual threat of two equally fearful, but seemingly opposed, destinies: unremitting banality and inconceivable terror.” More recently, Asma Nizami made a similar point on Twitter: “I personally think it’s really cool how we all went from learning how to make banana bread to learning how to abolish the police in a matter of weeks.”7 On one side of the coin there’s the terror of the coronavirus death toll, the exploitation of essential workers (inordinately people of color), the omnipresence of police brutality, the decoupling of financial markets from labor markets, the rise of global fascism, and a world literally on fire. On the other side there’s the banality of making a sourdough starter, playing Animal Crossing, doing Yoga with Adriene, watching Dianxi Xiaoge or, for us, Sudoku. It may seem impossible to hold the two sides together, but our rituals of play negotiate these seemingly opposed destinies. In 2020, completing a daily Sudoku and getting tear gassed are not as far apart as we’d think.

Sudoku is a numerical logic puzzle usually structured as a 9 by 9 grid bifurcated further into nine 3 by 3 sub-grids. To complete the puzzle, each row and column must contain the numbers 1 through 9. Each sub-grid must also contain the numbers 1 through 9. And no digit can be repeated in the same row, column, or sub-grid. Sudoku doesn’t have a particularly long history. It resembles ancient mathematical curiosities like Magic Squares8 and early twentieth century arithmetic puzzles that circulated in French newspapers before World War I. But Sudoku is primarily a 21st century phenomenon. Originally given the blunt yet descriptive name, “Number Place,” these types of logic puzzles were first codified by Howard Garns in the late 70s. Then they gained regional popularity in Japan via the Monthly Nikolist in the mid 80s when they were renamed with the equally straightforward title “Single Digit” or Sudoku. Finally, Sudoku was industrialized and published globally in the late 90s after the development of Wayne Gould’s Pappocom computer software for generating puzzles.9 We downloaded Pappocom the same day we got teargassed at a peaceful protest led by Oakland high school students. While recovering on our roof and trying out some of Gould’s randomly-generated puzzles, we watched police helicopters circling our building, broadcasting “This is the OPD. Get off the rooftops. Go inside.” Curfew pierces private space and it’s against the rules to solve Sudoku on your roof, one of the few places you can go these days (at least when the air quality index isn’t in the red.)

In the 2000s, Sudoku was quickly co-opted as edutainment, brain training, cognitive neuroscience, and anxiety management. On Psychology Today, pop psychologist and author of Total Brain Workout Marcel Danesi writes “[t]he satisfaction that comes from solving a puzzle seems to provide ‘relief’ from the large-scale puzzles inherent in everyday life.… They are a powerful form of escapism.… To paraphrase a well-known (and very sage) saying—an hour of crosswords or Sudoku a day, keeps the doctor (and everyone else for that matter) away.”10 So prior to the pandemic, Sudoku was already being imagined as a kind of quarantine media—a way to self-isolate through a single-player puzzle. Will a Sudoku a day keep Covid away? On nights when the OPD are out, or when the sky is orange, we turn the lights off at dusk and sit in the dark listening to the police as they roam outside our door. We worry about our neighbours. Are they inhaling tear gas or wildfire smoke inside their houses? We worry about our comrades in the street. If they’re arrested will the police let them keep their masks on? Will a Sudoku a day keep the cops away?

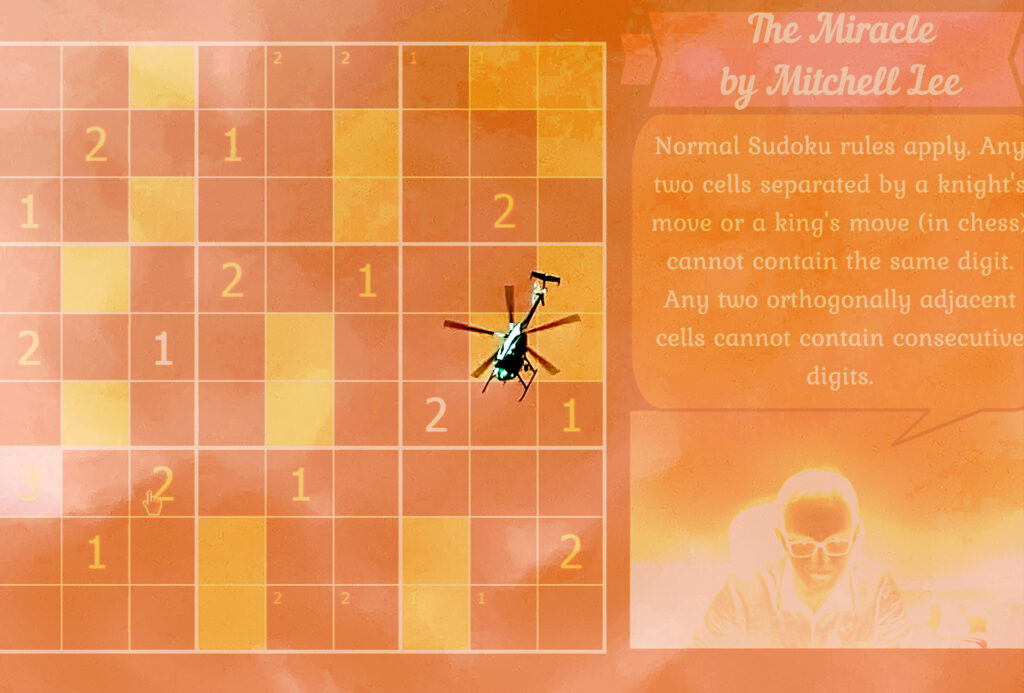

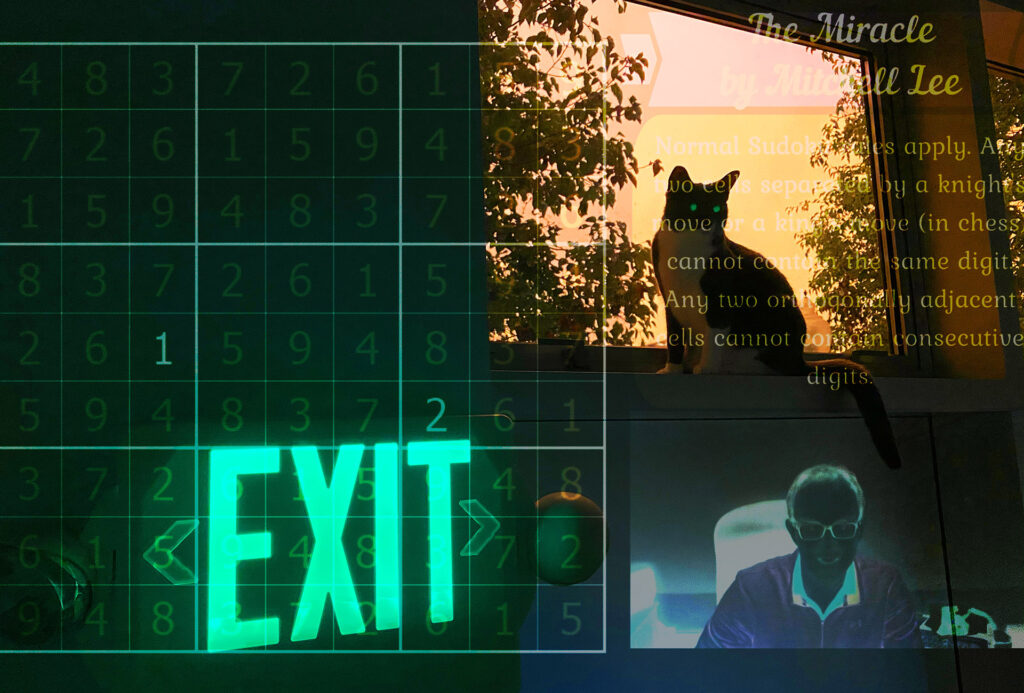

Danesi’s rhetoric of Sudoku as therapy is leveraged explicitly in the popular Cracking the Cryptic channel on YouTube. You might recognize that name from when their “Miracle Sudoku” video went viral.11 The channel is run by Simon Anthony and Mark Goodliffe, two UK puzzlers who regularly compete at the World Sudoku Championships. Although they’ve been quietly operating since 2017, their channel really took off during the pandemic, jumping from 5000 subscribers to 90,000. Tagged #self isolation, #quarantine, #antidote, #covid19, #cure, #boredom, #quarantinelife, #coronavirus, #vaccine and featuring titles like “The Puzzling Side-Effects of Covid-19”12 and “The Puzzling Antidote to Self-Isolation,” their videos often start with disclaimers.

The world is changing at the moment… over the last two years we’ve had probably ten emails from people who suffer from various forms of mental health [problems] and they’ve really found this channel to help them because it occupies their minds and gets their brain involved. At times when we’re [all] feeling a bit lonely, I think this channel could be useful to many of us.13

And it has been useful. Cracking the Cryptic combines one form of isolation media (Sudoku) with another (the Let’s Play) in order to produce a show that sits somewhere between cooking videos and speedruns. While we’re streaming Cracking the Cryptic videos sometimes the local news will get automatically queued. And suddenly we find ourselves watching Gavin Newsom’s Covid powerpoints or listening to Mayor Libby Shaaf and Interim Police Chief Susan Manheimer lie to us during an emergency press conference. We hear them defend the OPD’s use of force after they violently broke up the Oakland Tech high school demonstration a full 20 minutes before curfew even started. We were in that crowd. We saw what happened. Instead of continuing the gaslighting over teargas, we manually click back to Sudoku. You can’t lie in Sudoku.

In Sudoku there’s only ever one answer. And unlike the computer-generated grids in the New York Times or most printed puzzle books, following the puzzle designer’s logic in a hand-made sudoku is a two-player game. So we started playing along with the Cracking the Cryptic videos. The first thing we adopted was their use of Snyder Notation,14 a method where pencil marks are used only whenever a given number is limited to two places in a sub-grid. This skeuomorphic notation helps to not only remember where numbers can go but actively produces logical relationships between numbers. For example: when two matching sets of pencil marks align either horizontally or vertically, they suddenly have consequence in a third block. This is called an X-Wing. There’s also Y-Wings and XYZ-Wings which can cycle, chain, and loop. There are swordfish and jellyfish with and without fins. There are 3D Medusas, Death Blossoms, and Bi-Value Universal Graves. (Sudoku strategies are inexplicably metal.) As we learn the names of sudoku techniques, we also start to see these strategies taking place at the protests. Containment strategies. We can see the police setting up their lines. They’re looking up and down the rows and columns of Oakland’s streets. They’re making sub-grids. As we plan our lines of flight we see their flanking positions in the X-wing shape. Based on what corner we move to, they can tighten up their ranks and kettle us at any time. And every day they’re changing the rules and finding new constraints on how we can exercise our First Amendment rights.

Sudoku itself is also rapidly changing. There are many adaptations, variations, and mods of sudoku which add unique constraints beyond the original 1 through 9 in each row, column, and sub-grid. For example in Chess Sudoku15 a number cannot be repeated within a given chess move from itself, limiting repetitions inside the patterns of knights, kings, and queens. Sandwich Sudoku16 adds numbers on the perimeter of the grid signifying the sum of the digits sandwiched between 1 and 9 in each row or column. And something like Thermo Sudoku17 adds “thermometers”—arbitrary lines each terminating with a circular bulb along the length of which numbers must only increase.

The Cracking the Cryptic team has capitalized on these mods, quickly iterating on collections of hand crafted sudoku puzzles and releasing them in lightweight Unity apps. And, inspired by the post-Covid Sudoku boom and referencing Cracking the Cryptic’s “Miracle Sudoku,” Zach Gage and Jack Schlesinger built Good Sudoku,18 an app that not only includes a leaderboard so players could compete and contrast their methods, but also a reverse-engineered Sudoku solver to produce puzzles that require specific kinds of strategies. Whether it’s Good Sudoku, Killer Sudoku, Skyscraper Sudoku, Jigsaw Sudoku or even the elaborate Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time-themed sudoku puzzle hunt19 designed by ex-speedrunner Anees, there has been a rapid expansion of Sudoku mods as a result of the adoption of efficient solving algorithms like the Snyder Notation and the X-Wing we mentioned earlier. So we try to adapt as well. We started writing this essay with cop cars lined up outside our apartment. They use our street as a staging area for dozens of SUVs, with lights strobing, occasionally with sirens on. They’re making a Sudoku town to be organized, controlled, and quarantined. Each body isolated to a single cell. Our particular cell happens to be a block away from the Oakland jail. Because of the failure to protect prison populations from Covid-19 and because of California’s reliance on prison labor, the state now has a shortage of auxiliary firefighters. So we try and finish writing this essay under an orange sky.

Anna Tsing’s Mushroom at the End of the World is a 300-page tome that seems like a book about mushrooms but is really a feminist materialist philosophy on how to live and die in the Anthropocene. At the start of the book Tsing writes “[w]hat do you do when your world starts to fall apart? I go for a walk, and if I’m really lucky, I find mushrooms. Mushrooms pull me back into my senses…because they pop up unexpectedly, reminding me of the good fortune of just happening to be there. Then I know that there are still pleasures amidst the terrors of indeterminacy.”20 It could be mushrooms, or it could be family Zoom quizzes, Tiktok folk games, bird watching, Blaseball, online escape rooms, fortune telling apps… or maybe some Sudoku. Rituals of play are not the means to escape and find joys elsewhere, but a way to recognize that there are still moments of calm, control, and concentration here. Right here. Before stepping outside into air filled with teargas one day and wildfire smoke the next. Here we build survival strategies for living in an era of emotional and cognitive whiplash, where unremitting banality and inconceivable terror are inescapably bound to one another. Under the orange, gridded sky. “There is no there there,” only here here.21

Patrick LeMieux and Stephanie Boluk (Patrick, Stephanie) play, make, and write about games at the University of California, Davis. They are co-authors of Metagaming, co-creators of metagames like Footnotes and Triforce, as well as cast members on Every Game in This City.

Images authors’ own.

- Freeplay Independent Games Festival. “Rituals of Play in a Global Pandemic – Micro-talks (Freeplay ‘20).” YouTube. June 13, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jVKWhrs1SEM.

- The Oaklandside. “Orange Oakland: Photos and feelings from across the city on a very strange day.” The Oaklandside. September 9, 2020. https://oaklandside.org/2020/09/09/orangeoakland-photos-and-feelings-from-across-the-city-on-a-very-strange-day/.

- Boxall, Bettina. “‘Fires of hell’: How dry lightning has sparked some of California’s biggest infernos.” LA Times. August 23, 2020. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-08-23/drylightning-northern-california-fire-scourge.

- BondGraham, Darwin. “How 2 Oakland students got 15,000 people to march against police violence.” The Oaklanside. June 2, 2020. https://oaklandside.org/2020/06/02/how-2-oaklandstudents-got-15000-people-to-march-against-police-violence/.

- Lin, Sarah Belle, Darwin BondGraham, and Jonah Owen Lamb. “Did OPD violate its own policies against protesters? We investigated.” The Oaklandside. July 6, 2020. https://oaklandside.org/2020/07/06/opd-excessive-force-against-protesters/.

- Sontag, Susan. “The Imagination of the Disaster” in Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1961, p. 224.

- Nizami, Asma. “I personally think it’s really cool how we all went from learning how to make banana bread to learning how to abolish the police in a matter of weeks.” Twitter. June 6, 2020. https://twitter.com/asmaresists/status/1269336348630102018.

- “Magic Square.” Wikipedia. n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magic_square.

- Gould, Wayne. “Wayne Gould Puzzles.” Wayne Gould Puzzles. n. d. www.waynegouldpuzzles.com/sudoku/.

- Danesi, Michael. “The Appeal of Sudoku: Why is Sudoku an Obsession?” Psychology Today. Jun 19, 2009. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-workout/200906/the-appealsudoku.

- Cracking the Cryptic. “The Miracle Sudoku.” YouTube. May 10, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yKf9aUIxdb4.

- Cracking the Cryptic. “The Puzzling Side Effects of Covid-19.” YouTube. March 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e4dG5Ja9PXs.

- Cracking the Cryptic. “The Puzzling Antidote to Self-Isolation.” YouTube. March 19, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGOOzHCCh74.

- “Snyder Notation.” SpeedSolving.com Wiki. n. d. https://www.speedsolving.com/wiki/index.php/Snyder_notation.

- Studio Goya. “Chess Sudoku.” Steam. March 2, 2020. https://store.steampowered.com/app/1250560/Chess_Sudoku/.

- Studio Goya. “Sandwich Sudoku.” Steam. August 19, 2019. https://store.steampowered.com/app/1117310/Sandwich_Sudoku/.

- Studio Goya. “Thermo Sudoku.” Steam. May 25, 2020. https://store.steampowered.com/app/1316390/Thermo_Sudoku/.

- Gage, Zach and Jack Schlesinger. “Good Sudoku.” Good Sudoku. n. d. https://www.playgoodsudoku.com.

- Aneeslol. “OOT Randomizer Sudoku V1.06.” Bedibug. n. d. https://bedibug.com/sudoku/#/.

- Tsing, Anna. Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Stein, Gertrude. Everybody’s Autobiography. New York: Random House, 1937, p. 289.