This essay was originally published by The White Pube, 14 June 2020.

Emoji summary: 👩👦🌹👽

The garden died a few years ago with my granddad I think, and that makes sense to me. It was his space and workshop, somewhere he fixed bikes, watches, and painted everything he built the same shade of green. Now my hands are hurting—a whole blister on my palm—because I’ve been trying to reclaim his garden from the junk and the weeds that have grown around each other out there. If it wasn’t for all this new time in lockdown, the mess would have bloomed with rust and moss forever: trapped screws shut in Quality Street Tins and Roses too. But me and my uncle have been working on it for weeks now, sorting stuff out, re-flooring one half entirely, clearing the air. The long days are worth it for more space to while away the time. When quarantine started, my job was stopped, I couldn’t see my boyfriend anymore, and I went into full survival mode to try and protect Nan from coronavirus in her hospital bed downstairs. We haven’t had it yet and I really think it is a miracle she’s still here to be honest. But because she is, the whole house feels like it’s remembered to breathe out again. That blister is between the wisdom line and the life line on my right palm, and like lockdown, it is a little crescent in my fate.

Now that I have an inch of headspace back, I can see how my usual energy (for work) and affection (for Michael) are both being channeled into this project of: The Garden. I have really just never been bothered about this stuff before—about cleaning up a mess I didn’t make, about homemaking, or growing things and keeping them alive and well. (I have even been learning to cook, finally. I have actually started to care). Because I know if I don’t do the work, the garden will stay haunted; and if I don’t trickle water into my silly plants, they won’t be here anymore and I’ll miss them. I never realised living here and helping look after my Nan would mean so much, or how that meaning would come through in this way; how it would change me. The garden is a part of this new mood, of more people and things under my arms to care for. And I write about all this to start with because it’s what I’ve had under my fingernails since March, a context that has led me carefully into the flowery damp mood of Mutazione, the 2019 video game created by Die Gute Fabrik in Copenhagen and published by Akupara Games. I don’t know if anything else could have fit more perfectly into my life right now, and playing it felt like holding hands with a story because we were so close.

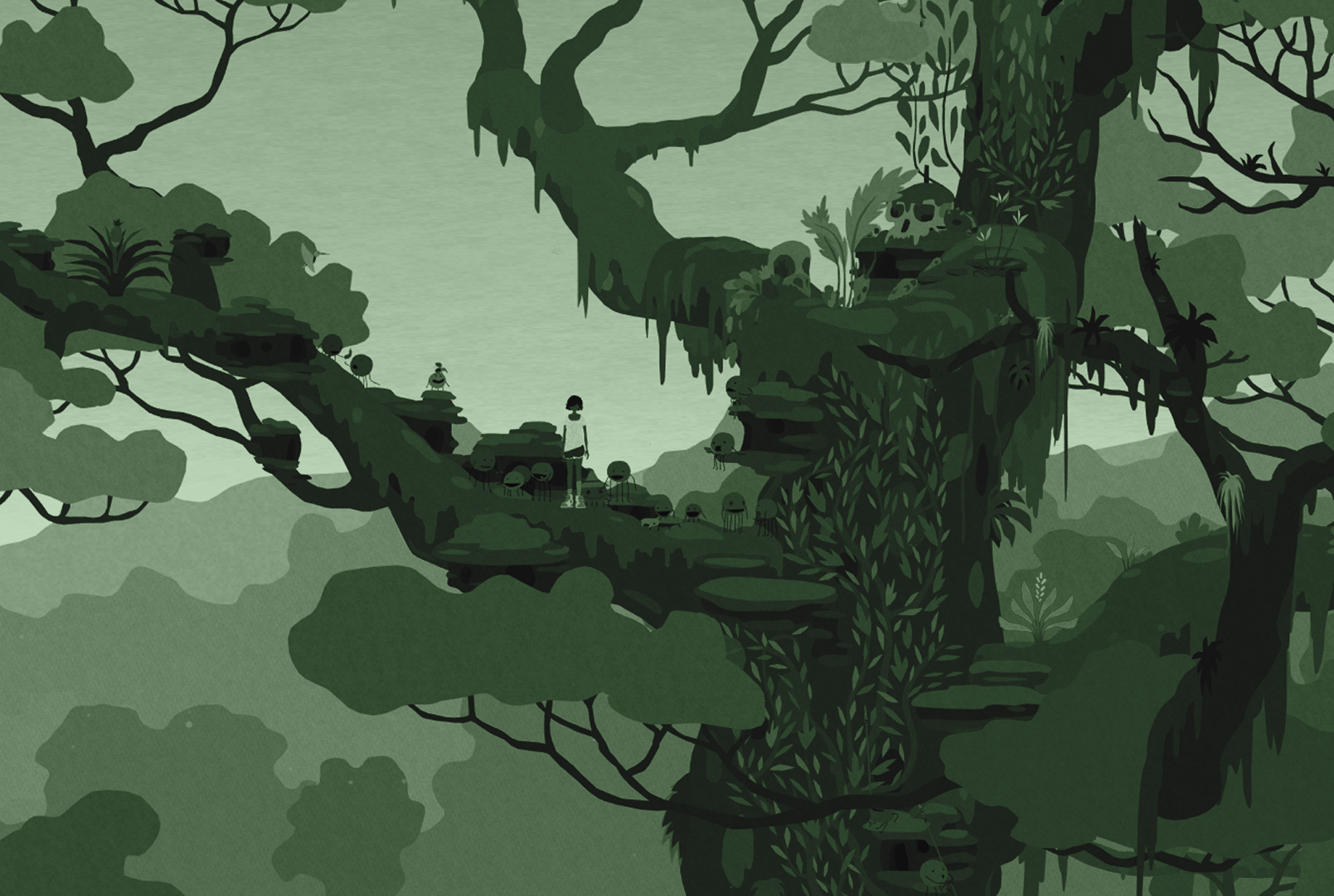

It’s only a short game that starts with protagonist Kai on a dock saying goodbye to her mum. She’s about to leave the mainland to go and look after her granddad, Nonno, who they think is at the very end of his life. Nonno lives on Mutazione, an island that was hit by a meteor called Moon Dragon that dramatically mutated the people and plants there. The people are vaguely human but changed: some have green skin, others have features like animals—fur, bug faces, ears like cats have on top of their head. There are creatures weirder still: the Dots are little balls with stick arms and legs that look straight off a Ribena advert, and there is this little lizard fella that loves playing on an arcade machine at the bar. The flowers they live amongst seem ancient, or alien and colourful. A tiny society ostracised ever since Moon Dragon hit them, they survive off the land, trading and mutual aid. Kai’s visit is significant because she’s the first outsider to come over in twenty years. She’s a tall teenager with short hair and brown skin; and she pops over in a baggy t-shirt, shorts, sneaker-head sneakers and bright green socks pulled up to different lengths.

When she arrives at his bedside, Kai speaks to her Granddad and is quickly pulled into his world: the interpersonal drama of the islanders, the past, the future, the research on their strange land, and all the problems that need solving—problems he could solve himself if he had the energy, but that Kai might as well learn to do now she’s here. He teaches her Mutazione’s trick, that plant types respond to songs in certain moods and grow fast before your eyes when they hear the right tune. Over the course of the game, Kai obtains all seven songs so she’s able to grow things to help some of the characters out, or create gardens just to make them feel better. And right, the day after I’d gotten to the end of the story and the credits were rolling, I watched a lecture on YouTube by the game’s writer, Hannah Nicklin, where she talks about how game designers should consider the player as a material they cannot pin down. One of her research questions has been: “What would games look like if we designed with or for you?” I’ve been thinking about that question a lot because Mutazione coincidentally catered to so much in my life. The parallels are not lost on me at all: that I am growing a garden to try to please my Nonno too, even if he isn’t here anymore; and I am looking after Kai’s Granddad with the same attention and worry as I am doing for my Nan downstairs, who is our queen and matriarch.

There is a scene one morning in the game where Kai goes to float in a secret lagoon with the island’s hunter Miu. Miu says: “I like the feeling of the water, like… vanishing me.” Kai replies, “I like the way water slows everything down. Like I have more control” and Miu ends by saying, “Everything is more deliberate.” Mutazione was that water for me, a pool with just enough resistance to push me to think about my family, myself, and my responsibilities: to go ahead and write all this text after completion. But I think this game is very generous in how its story has so many entry points for other players to process even more: inherited trauma, the figure of the monster, how we pass our histories down to the next generation, survival, adaptation, and closed networks and communities. The artwork makes the game a beautiful place to think about these things: like a European Ghibli aesthetic, but folkier. A trance-like place with petal rain and witch-thing Meteors in the sky.

The garden in the back of my Nan’s house used to be somewhere that was shared, but now all my aunties and cousins can no longer descend here of a weekend. It’s so empty. I’ve been lonely! But I am still finding every person past and present in these piles of artefacts I have to sort through before the garden can reappear. There are thinning bin bags of photos, water damage rainbowing out onto school portraits; and I found a shopping bag full of the magnets everybody had brought back from their holidays over the years. Wedding cake toppers, Christmas decorations, so many old ceramics. There was a broken pot with three odd earrings inside as well as a newspaper clipping congratulating my oldest cousin for finishing his A-Levels. We worked out it’s from eighteen years ago, but it’s still in perfect condition so I’m going to post it to him. I’ve even dug up some things from the dirt itself like bingo pens, crisp wrappers, and this tiny plastic bird that looks like a robin. My uncle recognised it immediately and said that when they moved into the house in the early 70s they found loads of these miniature birds buried in the garden and just never figured out why they were there. We’re so close to finishing, and I can’t wait for all our work to be done so I can lie down on new turf knowing I’m floating above the ghosts of a thousand plastic birds.

Gabrielle de la Puente (website, twitter, instagram) is a critic and curator from and based in Liverpool, England. She writes about games for The White Pube, a website she runs in collaboration with Zarina Muhammad. Gabrielle also runs OUTPUT gallery which works exclusively with artists local to Merseyside.