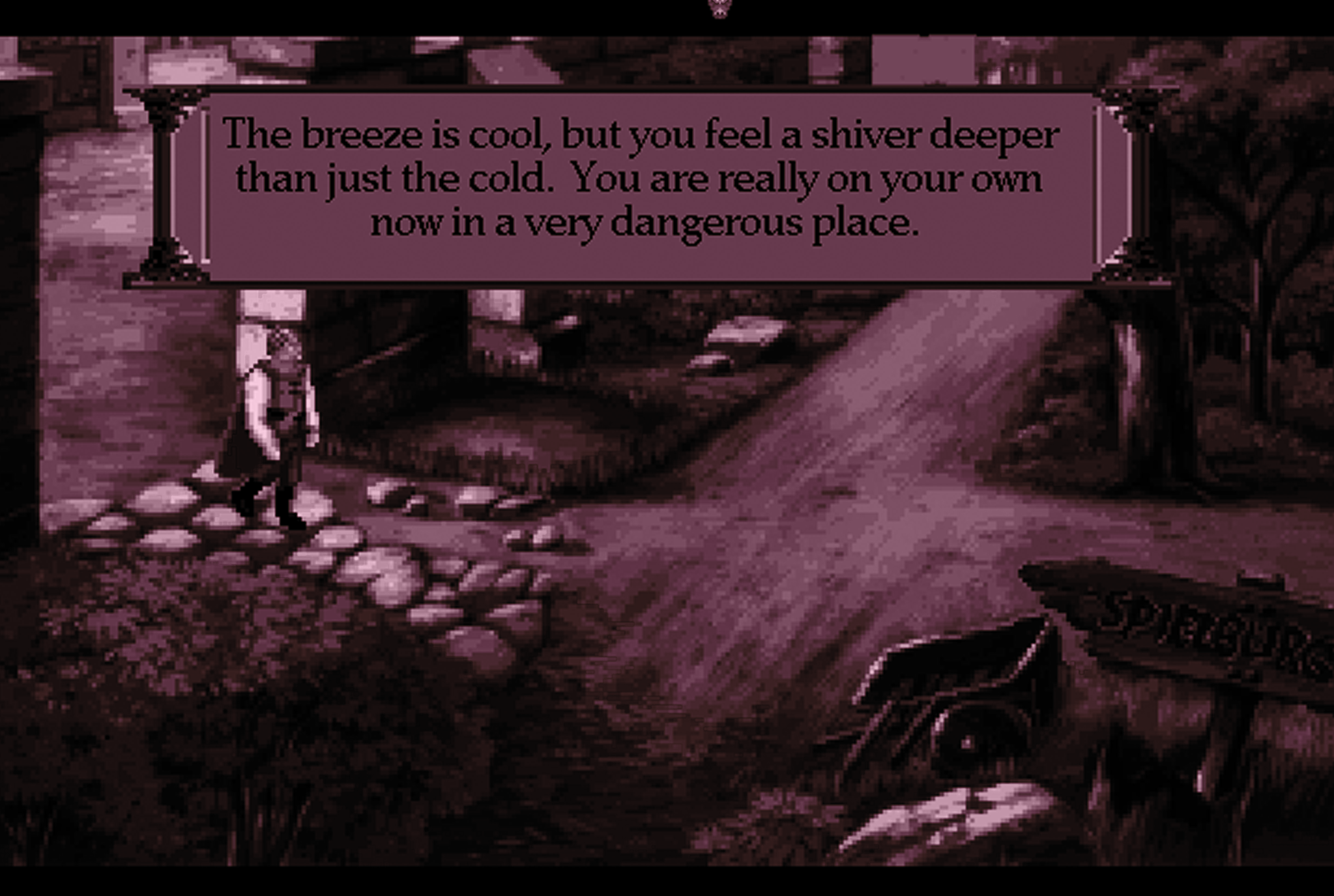

A baron sits alone in his castle, mourning his missing children. A friendly goon toys with a yo-yo. Brigands roam the forest, fortify their stronghold, make raids on the nearby town. A brown bear is shackled in a cave. A talking skull longs for a pair of glowing eyes. There is a sense of time standing still, of a town frozen in amber. Birds chirrup from the trees, the sun rises and sets, goblins attack and retreat according to invisible logic. And then… a hero arrives.

Like all youngest children, I grew up both in competition with, and also enthralled by, my older siblings’ tastes. There were six of us altogether—five girls, one boy. Through the blurred and shifting alliances of childhood, it was my brother I idolised most: four years older than me, unfailingly laidback, nerdy enough to hold LAN parties but not so nerdy as to be beaten up at school for it. I spent a lot of my childhood tagging along after him, thrilled to be involved with whatever he did. Bike-riding. Super-soaker battles. Playing video games.

There was one computer and a handful of games that we all shared. The one I liked best was Quest for Glory: So You Want to Be a Hero? Unlike Microsoft Flight Simulator (which bored me) and Doom (which inspired nightmares), Quest for Glory presented a world I could immerse myself in. Drawing on tropes and characters of fairy-tale and folklore and spiked with a goofy sense of humour, the game felt as exciting as the games I played in my backyard, all tree-climbing and homemade bow-and-arrows. Sitting alongside my brother, I perfected video game posture—hunched, cross-legged, transfixed by the screen—if not the game itself.

Five months, two lockdowns and countless anxiety spirals into the coronavirus pandemic, this is the posture I once again assume. The time for fussing over sourdough starter has passed. So has the urge to write a novel, master a language, or learn anything new. Outside, the streets are deserted. For six weeks, we can only leave our homes for essential reasons like grocery shopping, we must wear face masks whenever we are outdoors, we can’t travel further than five kilometres from our homes and we must observe a strict curfew which begins a little after the sun sets and lifts just before dawn.

Like a Gogol short story, the world outside has become a troubling combination of absurdity, tragedy and ever-changing rules: hundreds of the vulnerable die by the virus while politicians quarrel over the economy, and the healthy bemoan the inconvenience of being asked to wear a small piece of fabric over the face. I’m safe in my home, but being tormented by the three Furies of tedium, uncertainty, and the chatter of online conspiracy enthusiasts. What I need is something to gently—lovingly—disassociate into.

An idle search reveals that Quest for Glory is available online for a modest sum. A further search informs me that a benevolent nerd who goes by Paul the Tall (“Why?” he writes on his website. “Well, because I am quite tall—2.04 Meter”) has created a free program that will fool my MacBook into thinking it’s running MS-DOS so that the game will work. I download both.

The game’s premise is simple. You play as an aspiring hero, newly arrived in the barony of Spielburg, a once-prosperous town that has fallen on troubled times. The source of its misfortune is a curse, placed on the town by the ogress Baba Yaga after the local baron tried to exile her. The baron’s son and daughter have since gone missing; the mountain pass has been snowed in, cutting off access to the outside world; and a band of brigands, under the command of a mysterious leader, has been stirring up trouble. Your quest is to find the children, break the curse, and bring prosperity back to the land.

The world of the game is a bucolic one: you can spend days exploring the forests, where you might chance upon sparkling rivers and waterfalls, fairy rings, snow-capped mountains, fields of wildflowers. You might run into creatures friendly (wizards, centaurs, hermits), vicious (goblins, ogres, kobolds), or perplexing (bouncy blue orbs known as antwerps). If you happen across a monster, you can fight it—or you can just run away. The game offers up small side quests to undertake as you like: bring the town’s healer the ingredients she needs for a particular potion, help a fox caught in a trap, find a magical seed desired by a dryad. As I play, long-forgotten childhood memories begin to rise to the surface: how do I know I need to give twenty small, red apples to the Frost Giant so that in exchange, he’ll give me a glowing gem? I just know.

For weeks, I’ve been confined to my tiny apartment, staring out the window at the same slice of suburbia, speaking to no one, going nowhere. My brother and his partner live only a short commute away, but they might as well be in another land. I can’t visit them, or their new baby—my first and only niece—who has born during the first lockdown and who I’ve held in my arms only once. But it’s not the loneliness I mind so much as the uncertainty. I feel restless, dislocated. Depending on the spread of the virus, lockdown could last four weeks, six weeks, two months, a year. There doesn’t seem much point in making any plans. Less and less I put stock in the idea that things will go back to normal.

And yet, as I play the game, the dull background hum of the pandemic seems to fade. I wander through Spielburg’s arcadian forests, each screen verdant and lush and alive with the sound of birdsong. My brain seems to process it the same flawed way it recreates childhood memories: impressionistically and in Technicolor, each moment threaded with the warmth of nostalgia.

By modern standards, Quest for Glory is simplistic: the animation janky, the point-and-click gameplay laughably unsophisticated. Today’s most high-profile games tend to reach for fidelity to real life, trading in moral complexity and variable outcomes. I want the opposite of that. I want to be led through a perfect, narrow path to a perfect conclusion. I want to be able to reboot, start over. I want to remember the world how it was, when I might slouch carelessly shoulder to shoulder with my brother, engrossed in play. Amidst the bleak, unending turmoil of life under Covid-19, I want something entirely predictable.

The game delivers. I play slowly, letting the quests unfold without urgency, mapping the game’s borders, its definite edges. There is comfort in re-treading these familiar paths, just as there is comfort in reaching, finally, the longed-for ending. The hero triumphs. The children are reunited with their family. Once again, prosperity returns to the land.

Nadia Bailey (website, twitter, instagram) is a writer and editor based in Melbourne, Australia. She is the author of several books on pop culture, most recently Frida A to Z: The Life of an Icon from Activism to Zapotec. She is currently working on her first novel.