At the end of the 2019 high school football season, Grandview Heights Bobcats Head Coach Jason Peters knew 2020 would be a tough one on the gridiron. Eleven of his total 39 players were graduating, leaving a giant hole in team leadership and multiple vacancies in key roles on both sides of the ball.

“All of our skill guys on offense — quarterback, running-backs, receivers, they were all going to be new. And on defense, our entire secondary, they were going to be new,” he explained. “We knew as a coaching staff that it was going to be a challenging year because we were going to be so young at key positions.”

Then came Covid-19. And the difficulties Coach Peters thought he would face in 2020 became laughable.

American football is a complicated sport. For the purposes of this story you only need to know three things: learning to play it correctly and safely involves months of practice; every single play requires close contact between teammates and opponents; and in big cities and small towns across the United States, high school football is akin to religion.

That is certainly the case in Grandview Heights, Ohio, a 1.3-square-mile city of about 7,000 that lies within throwing distance of the city of Columbus, the capital of the state. At typical Grandview Heights High School football games, as dusk settles in late summer and early autumn, the bleachers in Anderson Field, where the Bobcats play, are packed. Students, parents, family, alums, and locals are all ready to cheer for the players and jeer the officials under what is known across the country as the “Friday Night Lights.”

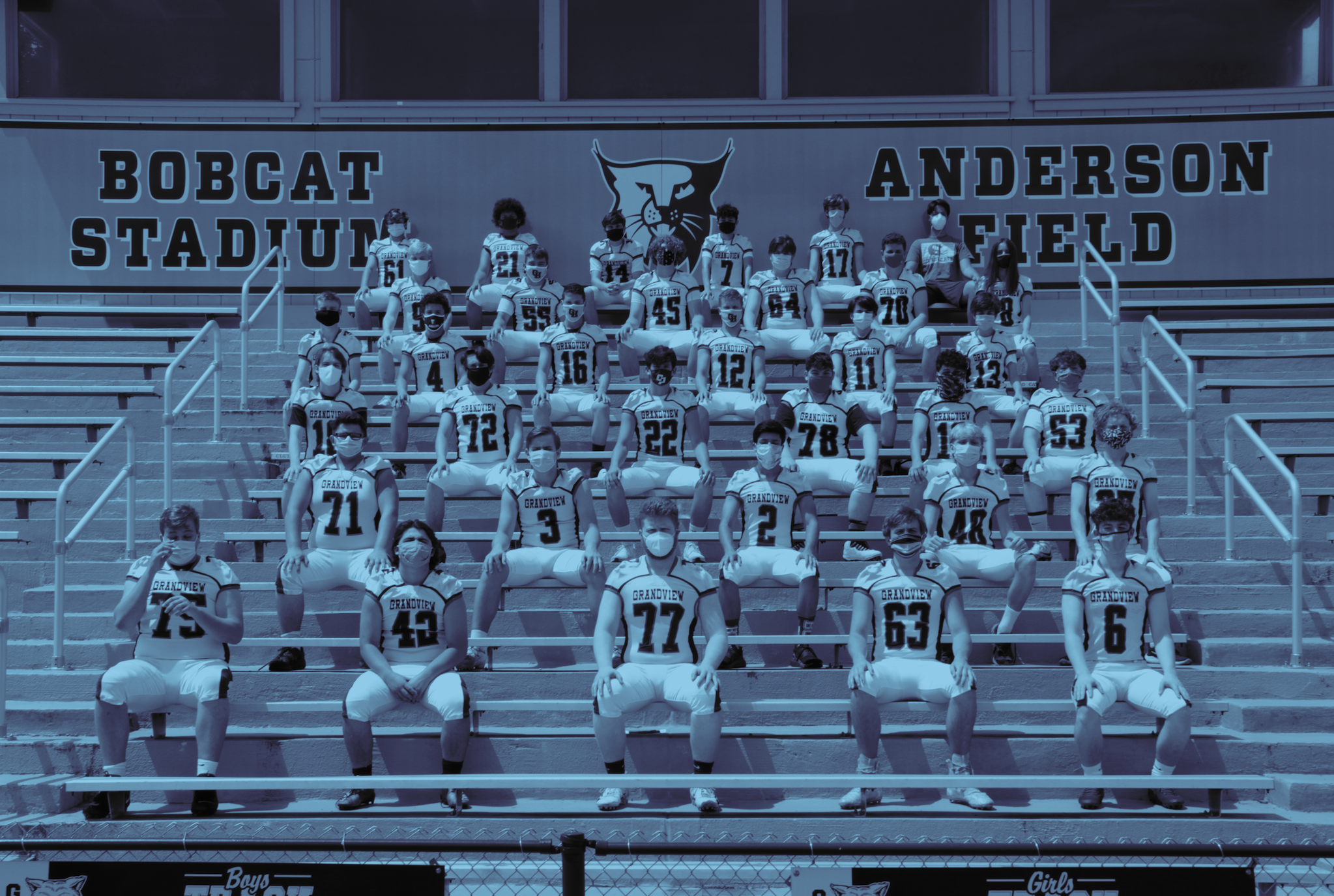

2020 saw me preparing for my “christening” into this mayhem. I’m not a football fan. Growing up, I never saw the lure of the sport or the fun in hanging out at the football stadium with my classmates during games. But I was definitely in the minority. And, as the cyclical nature of life shows us time and again, my chances of being part of the Friday night football tradition weren’t lost after all. My sixteen-year-old son, Lachlan, had lobbied me for the better part of five years for permission to play football. I worried about his safety given the reputation football has as a brutal sport. But my baby boy had grown into a nearly six-foot-tall, 230-pound young man: built to play the game, many people told me. This year, I relented and he eagerly signed up to play for the Bobcats in his junior year of high school. And I swallowed my fear, bought myself the requisite Grandview Heights Bobcats Football sweatshirt, and prepared to support the newest member of the team’s defensive line and his teammates from the steel bleachers of football stadiums across central Ohio. Who knew I’d also need a matching mask to do it?

Shut it all down

Ohio Governor Mike Dewine was one of the first state leaders in the country to act on the grim reality of the novel coronavirus by issuing statewide stay-at-home orders — canceling events, shuttering restaurants and bars, and closing schools in mid-March 2020. Students attending universities throughout Ohio were sent home and all pre-, primary, and secondary schools were closed, including Grandview Heights City Schools.

As the pandemic was beginning to take hold in the states, the GHHS Bobcats basketball team were celebrating a fantastic season, having won their seventh district championship and third since 2016. They were in the midst of playing for a statewide title when the season was abruptly cancelled due to the pandemic. The players were devastated, especially seniors graduating in May, who were competing in the final games of their high school careers.

“A lot of the seniors [on the football team this season] played basketball as juniors, and I talked to them, and I saw how it physically hurt them when they had those opportunities to play taken away from them,” Peters said, visibly tearing up. “It means a lot more than what a lot of us think it does.”

That fueled his desire to ensure that his football team would get a chance to face off against an opponent along the fifty yard-line on the turf and under the lights at Anderson Field that fall.

Personally, though, Peters was facing his own battle.

For love of the game

A tumor was discovered on his kidney that winter. Fortunately, the prognosis was as good as it can be in such a situation and he was slated for surgery to remove the cancer in late March. At the same time, the pandemic was spreading like wildfire across the country. Hospitals, already feeling the strain of the onset of Covid-19 cases and the pinch from a shortage in supplies like surgical masks and ventilators, began canceling non-life-threatening and elective procedures to shore up resources for the onslaught.

The difference between Peters standing on the sidelines for his team’s first game of the 2020 season in August, if they could even have one, and following a very different path was literally a weekend. “The Friday before we went on lockdown was when I had my surgery. So, if it was scheduled for Monday, it wouldn’t have happened,” he said. “I just got in under the wire.”

He did not require follow-up treatment like radiation or chemotherapy to treat his cancer, but still, he recognized that he faced greater danger related to potential exposure to the Coronavirus than others in the population.

“I talked to my doctors and I said, ‘Here’s the deal, this is what I do. This is what I love, this is who I am. It’s my passion. I don’t have a lot of hobbies outside of this.’ And the doctor told me to be safe, be smart, and don’t be stupid about the virus and I’d be fine, and, knock-wood, everything’s been okay,” he said, rapping his knuckles on the table.

Sometimes, practice doesn’t make perfect…

After a long spring, Covid-19 case numbers were finally on the decline in Ohio and hope was starting to creep up after three months of the darkness of daily death tolls. In early June, the state began slowly opening back up and restrictions began loosening, including those on children conditioning for sports — with a lot of caveats. Masks had to be worn at all times, work-outs had to take place in pods of not more than nine and social distancing, temperature-taking and other protocols were put in place to try to prevent transmission of the disease.

Football is a high contact sport, tackling an art that must be taught and practiced. In the absence of being able to work on that skill, Coach Peters and his staff focused their players on running, weight-lifting, and classroom work reviewing plays during daily practices.

No one minded.

“It was like being reborn for some of these kids,” Peters said. “We still didn’t know if the season was going to happen, but just getting them out of the house and getting them together and giving them an opportunity to do this, that was good for them.”

But the rules made creating a consistent, regimented training program difficult. That, and the no-contact practices, would come back to haunt the team. Senior Matthew Taylor, 17, pointed to the lack of weight-lifting while the state was under lock-down orders as a reason for the injuries that plagued the Bobcats during the season.

Taylor has played for Peters for four years at GHHS. His football career started long before that, though, in grade five. As one of the most experienced and senior members of the team, he is a natural leader. The one idea he tried to hammer home to his 35 Bobcats teammates throughout the season was perseverance. “It’s something that can be cemented in these younger guys’ heads if they consistently do it,” he said.

It’s a fitting theme for anything taking place during the time of the Coronavirus, especially as cases spiked and dropped throughout the summer, each time taking with them a little hope that Bobcats football would be a reality in 2020.

But Why?

It’s important to ask the question, why would anyone want to risk their health for a game? Why would parents be willing to risk their child’s health, and that of their entire family? Why would a city or state be willing to gamble that everyone involved would follow the strict guidelines put in place to make the game as safe as possible?

The answer is complex and changes in hindsight. My son felt it was important because sports play a big role in teens’ lives and without them, something would be missing. Peters felt it provided a sense of normalcy — even if there was nothing normal about the way they played football in 2020.

According to Gov. DeWine, at the August 18 press conference during which he issued the orders that allowed fall sports to move forward in the state, a lot of factors were taken into consideration.

He acknowledged that with increased exposure — from games or from in-person school even — came increased risk of spreading the virus. “On the other hand,” he said, “we all know the importance of sports. We’ve seen that, [Ohio First Lady] Fran and I have seen that with our own children. We’ve seen it with our grandchildren. Sports matter. It makes a difference. Sports provide all the things that we know — discipline, it brings order, structure in the lives of student athletes and certainly it brings joy to those athletes and their families. Any decision about playing sports or not playing sports cannot be made in a vacuum. That young person, if they’re not playing sports, obviously will be doing something else with their time and that has to be kept in mind as well.”

From a personal standpoint, I wasn’t wild about the idea. But when I assessed the chances my family had for exposure to Covid-19, contact sports actually fell low on the list. First there was my husband, who works in a hospital. Second was Lachlan’s part-time job, working the drive-thru lane of a local restaurant a few nights a week. Third were my weekly trips to the grocery store, where multitudes of people flouted the mask and social distancing guidelines. At least at football every child entering the practice field was being checked for symptoms and the team itself, coaches and players, was under a lot of scrutiny. When rules were broken, even by accident, rebukes were swift.

Even so, the peril wasn’t lost on anyone. Lachlan and his teammate Matthew both said that playing felt risky at times throughout the season.

“During a game it’s scary knowing I’m trusting strangers,” Taylor said.

“Sometimes, during a game, you’d hear someone cough and get scared,” Lachlan said. “But that was just part of the game.”

We make plans and God laughs

The Bobcats practiced throughout the summer, with stops and starts along the way as exposures occurred; protocols were massaged; and state, regional, and local officials tried to put some sort of plan in place to get students back into the classrooms and onto the playing fields.

The Ohio High School Athletic Association, the governing body on secondary school-based sports in the state, was tasked with making a recommendation to the Governor and Lieutenant Governor on whether there could be a fall sports season and what protocols should be followed to make it safe. Once they gave the okay, it was up to the folks on the ground to figure out a way to actually do it.

Peters described the time leading up to the season as a flurry of reading best-practices suggested by health and academic agencies, following government press conferences, emailing school officials, and meeting with Grandview Heights Athletic Director Brad Bertani on Zoom. “It was really understanding what and why and how we do things to make it as safe as we could for the kids and give them the opportunity that we wanted to give them,” he said.

Once they devised a plan, and revised it numerous times, it had to be approved by the school board before a season could even be scheduled.

But opportunities were already slipping away from the Bobcats.

A band of brothers

Aside from needing three months to train their bodies and minds for the physicality and mental intricacies of the game of football, Coach Peters puts his team together in early June so they can bond. On offense, football requires players to protect their teammates from crushing tackles from opponents looking to stop the ball from advancing down the field. On defense, those same players are doling out the brutality. Anyone with the ball is a target. To be willing to use your body to move the ball or protect those charged with that task requires a lot of sacrifice. The closer you are as a team, the more you’re willing to give.

Bonding begins in summer practice. And it continues as players tick off all of the rites of passage of playing high school football: conditioning, getting fitted for pads, the first practice in pads, the first day of full-contact practice, and so on. But to many GHHS players, team bonding culminates before the season even begins during the annual Camp Bobcat retreat. There, players descend on a farm in southern Ohio to spend a few days playing football and a few nights sleeping under the stars. “Our summer camp is always a highlight of the

season,” Taylor said.

In 2020, the threat of Covid-19 meant there was no Camp Bobcat. And the go-ahead for full-contact practice came with just a few weeks before the start of the season, leaving no one properly prepared for actual game conditions.

For the game itself, the rules put in place were “little things,” Peters said. Before Covid-19, players drank from communal water bottles during games. Now, there’s a cooler stocked with single-use mini-bottles of water that players drink instead. Prior to the pandemic, it was common to see a gaggle of players standing on the sideline, right behind the coach, watching plays unfold on the field. Now, anyone not playing in the game must observe six feet of social distance while on the sidelines. It’s a strange sight to see young men stretched out from end-zone to end-zone, like chess pieces waiting to go into battle. There’s also a new addition to the traditional navy blue and white Bobcats football uniform — a charcoal grey gaiter, which must be worn over the mouth and nose at all times except when a player is actually in the game. A common refrain heard on game days was, “No gaiter, no game.”

In an attempt to prevent transmission of the disease, the officials refereeing the game no longer touch the ball, instead throwing down an orange beanie where the football should go and leaving the

responsibility for placing it there to players. Each team uses their own ball when on offense.

Not all of these changes are bad.

Missy Baker, whose twin sons Logan and Maddox are sophomores and second-season starters for the Bobcats, is happy to do away with the shared water bottles. “Let’s agree that whether it’s Covid or not, they shouldn’t be doing that,” she said.

Peters admitted he enjoyed the extra space the social distancing rules gives him and his staff on the sideline. Taylor disagrees. “The sideline rule doesn’t allow for the [players on the] sideline to get as into the game,” he said. He does not see any benefits of the new rules.

Practices are tightly controlled as well. Players are required to wear masks, have their temperature taken before entering the practice field and answer a spate of questions fired off by Coach Peters in drill-instructor manner. Every night, the locker room, training room and office at the stadium is deep-cleaned and sanitized with a machine called the “Tornado-Vapor.” Any player experiencing Covid-19 symptoms has to be tested and those exposed to Coronavirus are quarantined. The Bobcats had a few players quarantined and one test positive — but the collective diligence of the coaching staff and players prevented an outbreak on the team.

“It was made very clear to us under no uncertain terms that if we didn’t follow the guidelines, we could get this taken away. And the last thing I ever want to do is take an opportunity away from a kid,” Peters said.

Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire

High school football is about more than the play on the field. It’s about tradition and teammates and those Friday night lights. And that’s where the changing rules of play impacted the 2020 Bobcats the most.

On typical Thursday nights there is a team meal, dubbed “the spread.” Fridays, before the game, there is a team dinner. During half-time, players enter a locker room pumping with music and decorated by a committee of parents to create a party-like atmosphere. After games, that same locker room would fill with well-wishers, congratulating the players on a game well-played. There is a three-day community “Ox Roast” in September, which features the team marching the half mile from the school to a local park, where senior players get the honor of lighting the traditional bonfire. There are fundraisers and pep rallies and Meet the Team nights. There is an end of the season banquet. But none of that happened in 2020.

“It’s all of these little things that, to me, help make the program a little special, a little different than what everybody else does… and gives the kids special experiences,” Peters, who has coached the team for fourteen years, said. “That’s really what we’ve lost, what we’ve had to stop. And that’s hard.”

For Taylor, all of those things help hype up the players for the game, and that’s sorely missing in 2020. As are the capacity crowds numbering near 1,500, packed together tightly on the bleachers, doing the “Bobcat Rumble” along with the cheerleaders, and lending their energy to the team.

The OHSAA severely limited the number of people who could attend high school football games this season. Two tickets were issued to each player and guest names went on a list for contact tracing. Those attending had a strict set of rules – observe social distancing in the stands, wear a mask at all times, and disperse immediately once the competition ends.

Gone were the stands filled with players’ extended families, the student section overflowing with teenagers sporting their team colors, the neighbors socializing over concession stand food, the marching band performing their halftime show. In their place was an eerie silence, punctuated with game updates by the in-stadium announcer and frequent reminders to wear a mask and stay six feet apart. Occasionally, a member of the school janitorial staff or another volunteer would make their way through the stands, bottle of disinfectant and rag in hand, to wipe down the hand rails in the bleachers.

It took a toll on players’ families. “Parents are struggling to get

tickets,” Baker said. “And it’s hard not being able to bring other family members besides our own.”

I didn’t see the first game because it took place at another school and they limited visiting players to one ticket each. During the regular season, I skipped a home game to allow my brother-in-law, a former high-school football player who still follows games some thirty years later, to attend and watch Lachlan play. Even with my limited exposure to high school football in the past, it was clear that 2020 games were dramatically different. It was quiet in the bleachers at Anderson Field. Everyone was cordial, nodding a head, smiles invisible under masks, when taking a seat, but for the most part everyone kept themselves to themselves. It felt like even cheering after a good play was against the rules.

But the people who really noticed were the players.

“Players aren’t as focused when they arrive,” Taylor said of the lack of fans in the stands. In prior seasons, he said, the atmosphere was electric. “You walked into the stadium and you could feel the energy of the fans in the stadium and the players fueled off of it.”

Clear eyes, full hearts, can’t lose

After all of the virtual meetings, false starts and pandemic-related pauses, changed rules, broken traditions, injuries, and more than a few misplaced masks, the Grandview Heights Bobcats were, in fact, able to have a 2020 High School Football season. They went 0-9.

And while it would be easy to blame Covid-19 for their less-than-stellar performance, Coach Peters isn’t one to offer excuses.

“We haven’t had a great season. We’ve had injuries and we’ve had issues and you know, we’re not a great football team right now,” he said bluntly. But, as he told the players after a particularly tough 50-7 loss to Buckeye Valley High School, he’s never been prouder of a team.

“These kids just keep showing up and busting their asses,” he said, voice breaking slightly. “They just keep showing up. That’s why I do what I what I do. It’s not about wins and losses, it’s about the relationships I can build with these kids and how I can help them in life.”

The pandemic robbed the 2020 Bobcats of a lot of opportunities. It would be easy to say that getting to play football at all in this climate is a lesson in gratefulness these young men will carry with them throughout the rest of their lives. But Peters believes that his players learned something even more important.

“I think this really gave our kids a greater appreciation for enjoying the moment,” he said. “Rather than thinking ‘this is just another practice,’ they learned that this could literally be their last practice…It’s a tough lesson for kids, because all high school kids can think about is ‘I wanna graduate and get out of here.’ But it’s like — no, stop and smell the roses man, because if you don’t, life’s going to pass you by. Let’s not just throw away these four years. Enjoy them.”

Joy Frank-Collins (website, Twitter, Instagram) is a freelance writer based in Columbus, Ohio. Her byline is included in many local, regional, national, and international publications, most recently: Columbus Monthly, Pittsburgh Magazine, and various online platforms for the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). She is currently editing her first novel and working on a collection of essays tentatively titled Finding Joy: A Memoir of the Mind-Blowing and Mundane Moments of Modern Middle Age.

Images author’s own.